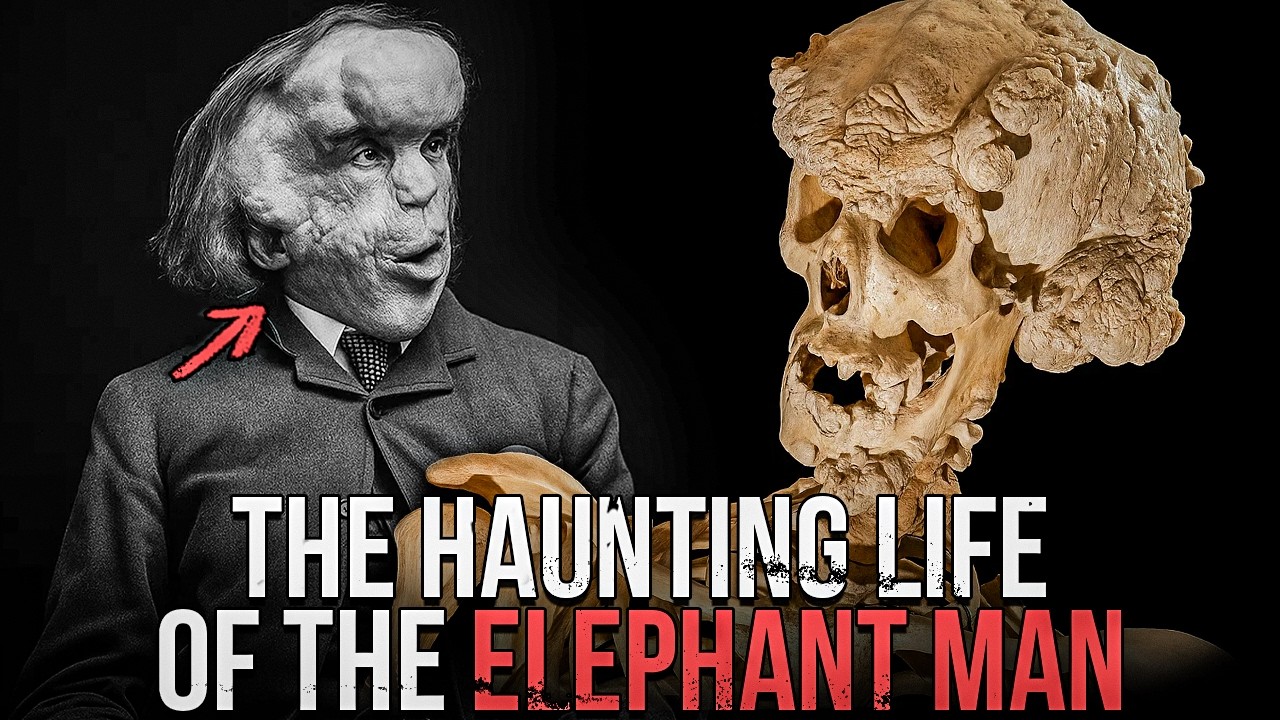

The Surprising, Sad, And True Story Behind ‘The Elephant Man’

On a cold April morning in 1890, attendants at London Hospital entered the small private room of a 27-year-old man and froze. There were no signs of violence, no struggle, and no apparent cause of death. Yet what they saw was so haunting that it became one of the most disturbing cases in Victorian medical history.

The body on the bed was that of Joseph Carey Merrick, known to the world as The Elephant Man. What shocked doctors most wasn’t that he was dead—but that he was lying flat.

For Joseph Merrick, lying down meant certain death. His massive skull, weighing more than 11 pounds, would crush his airway if he tried to rest like an ordinary man. For years, he had slept sitting upright, his knees tucked beneath his head. Yet on that April morning in 1890, Joseph had finally dared to do what most of us take for granted—he tried to sleep like everyone else.

It was the act that killed him.

A Normal Child in Leicester

Joseph Merrick was born on August 5, 1862, at 50 Lee Street in Leicester, England. His parents, Mary Jane and Joseph Rockley Merrick, were working-class Baptists. By all accounts, his birth was normal. He was a healthy baby—pink, strong, and perfect.

But before he was two, small swellings appeared on his lips. Soon his skin thickened, his right arm grew larger than his left, and a bony lump pushed through his forehead. Doctors were baffled. Victorian medicine could not explain his rapid and grotesque transformation.

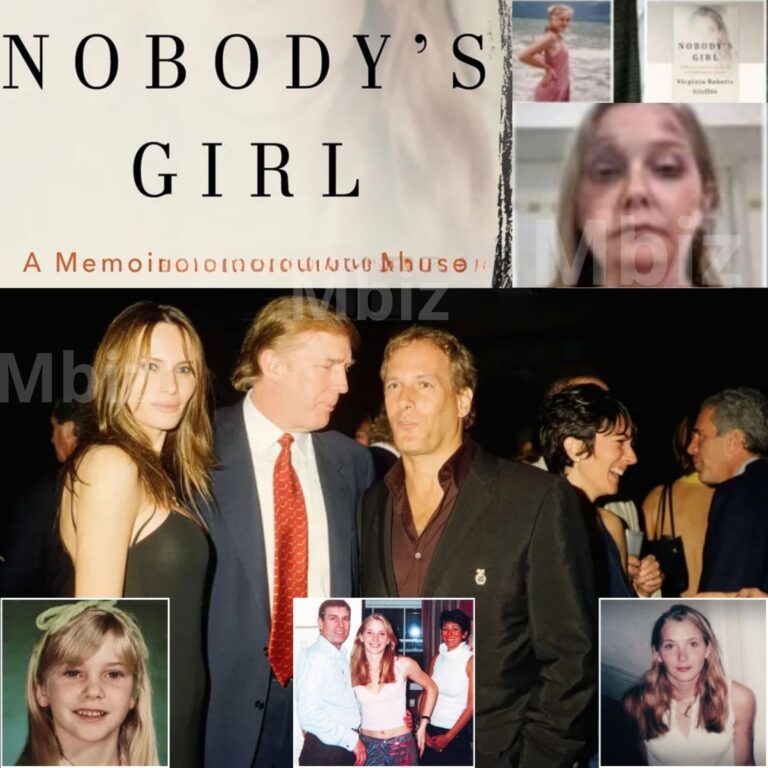

Mary Jane, desperate for meaning, turned to superstition. When she was pregnant, she had been startled by a passing circus elephant. In an age that believed a mother’s emotions could shape her unborn child, she became convinced the fright had “marked” her baby. The legend of the Elephant Man was born long before the world ever saw him.

A Mother’s Love—and a Descent Into Misery

Mary Jane adored her son, teaching him to read and soothing him when cruel children hurled rocks and insults. But when she died of pneumonia in 1873, Joseph’s fragile world collapsed.

His father quickly remarried. The new wife, Emma Wood Antill, saw young Joseph as an embarrassment. “He will work for his keep,” she said—and she meant it.

At thirteen, Merrick was pulled from school and forced to labor in a cigar factory, his enormous right hand barely able to grip the delicate tobacco. When his deformities made work impossible, he became a street peddler, knocking on doors to sell trinkets.

Imagine the scene: a boy with a monstrous face, half-hidden beneath a scarf, trying to speak through distorted lips while strangers slammed doors and screamed. Children cried. Adults recoiled. Police received complaints that he frightened passersby.

When his license to sell goods was revoked, his father beat him brutally and threw him into the street. Merrick was only seventeen. Homeless, penniless, and rejected, he wandered the freezing alleys of Leicester until an uncle took him in—briefly.

By 1879, the family could no longer support him. Merrick was sent to the Leicester Union Workhouse, one of the grim warehouses of human misery that Victorian England used to punish poverty. There, amid disease and despair, he toiled in silence for four long years.

The Birth of “The Elephant Man”

In 1884, Merrick made a desperate decision. If society viewed him as a monster, perhaps he could survive by becoming one.

He contacted a showman named Sam Torr, offering himself as a living curiosity. Torr agreed. Soon, Joseph was touring with a small troupe of “freak show” performers under a new stage name: The Elephant Man.

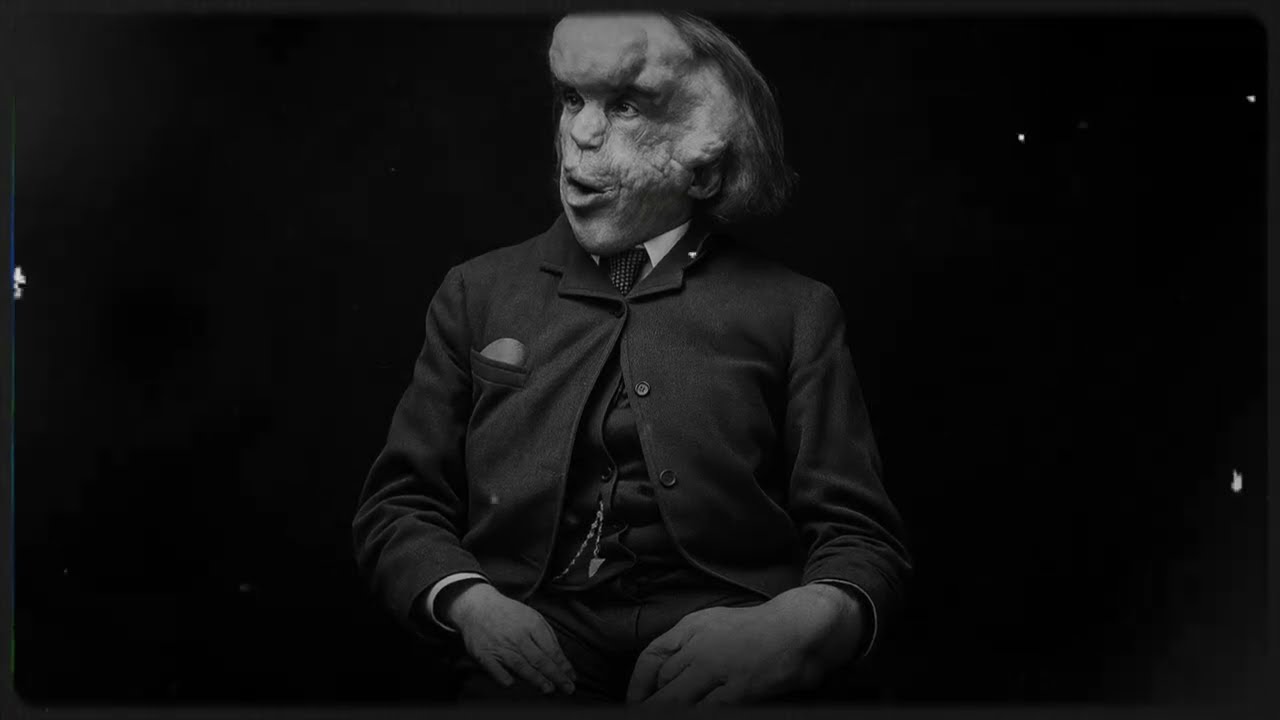

Posters exaggerated his condition, depicting a half-man, half-elephant creature. The reality was horrifying enough: his head twice the normal size, his mouth twisted, his skin covered in bulbous growths. Yet behind the curtain, Joseph was polite, gentle, and articulate—traits audiences would never see.

The exhibitions spread from Leicester to Nottingham, then to London. By winter, he was being shown in a rented shop on Whitechapel Road, just across from London Hospital. The manager, Tom Norman, ran the show like a grotesque theater. He would stand outside shouting, “Ladies and gentlemen, behold the most extraordinary human being ever to walk the earth!”

Inside, Joseph sat motionless on a stool, wearing only a cloth around his waist. The stench of decaying tissue mixed with candle smoke as horrified onlookers stared in silence, some fainting, others crossing themselves in fear.

It was there, across the street, that a curious young surgeon first heard of him. His name was Frederick Treves.

The Doctor and the “Monster”

Treves was thirty-one, ambitious, and fascinated by medical oddities. When a medical student urged him to see the Elephant Man, he crossed the road to Norman’s exhibit. What he saw changed both their lives.

Treves arranged to examine Merrick privately at London Hospital. To prevent a mob, Joseph was disguised—cape, hat, and a burlap sack covering his face.

During the examination, Treves noted that Merrick’s skull circumference measured 36 inches, his right arm was grotesquely overgrown, and his skin hung in thick folds “like curtains of flesh.” Yet despite his appearance, Treves was struck by the intelligence in Joseph’s eyes.

At the time, Treves wrongly assumed Merrick was “an imbecile.” He would soon realize how mistaken he was.

Exploited, Then Abandoned

Treves presented Merrick to the Pathological Society of London, exhibiting him before a hall of physicians as if he were a medical specimen. Joseph endured the humiliation in silence. But when the police cracked down on freak shows shortly after, his livelihood vanished.

His handlers fled to continental Europe with him in tow, hoping to evade British authorities. Instead, they robbed him of his savings and abandoned him in Brussels.

Hungry and destitute, Joseph somehow found his way back to England. When he stumbled off a train at Liverpool Street Station in June 1886, he was barely recognizable—starved, terrified, and unable to speak. A crowd gathered, jeering.

The police found only one clue on him: a crumpled business card with Dr. Frederick Treves’s name.

Treves came at once. Seeing Merrick’s condition, he brought him back to London Hospital—not as a specimen this time, but as a man in need of rescue.

The Hospital Years: Finding Humanity

Hospital rules forbade the admission of “incurable” cases. Merrick had nowhere else to go. But when the story reached the press, the public responded with extraordinary compassion.

On December 4, 1886, The Times published a letter appealing for funds to help “a man of singular affliction.” Donations poured in from across Britain. Within weeks, there was enough to give Joseph a permanent home inside the hospital.

Two small rooms were fitted for him: a sitting room and a bedroom, furnished low so he could reach everything, and—at Treves’s insistence—without mirrors.

At last, he was safe.

To Treves’s surprise, once Joseph’s speech was understood, he revealed himself as an articulate, sensitive, and deeply thoughtful man. He loved books, the Bible, and poetry. He could read, write, and dream.

He told Treves he wanted, more than anything, “to be like other men.”

The Kindness of Strangers

Word of the Elephant Man’s transformation spread. Famous Londoners visited, bringing gifts. Actress Madge Kendal became his benefactor, sending letters, photographs, and money.

When Treves arranged for a gentle young widow, Leila Maturin, to visit, Joseph wept. “She was the first woman ever to smile at me,” he told the doctor later. He wrote her a letter in his elegant hand:

“The partridge was splendid. With much gratitude, I am truly yours,

Joseph Merrick.”

He began crafting models of cathedrals from paper and card, masterpieces of precision that still exist today. One, a replica of Mainz Cathedral, was described by Treves as “a marvel of patience and skill.”

Joseph’s most joyful moment came in May 1887, when Princess Alexandra, wife of the Prince of Wales, visited the hospital. She shook his hand without hesitation and sent him a Christmas card every year thereafter.

For a brief, shining moment, Joseph Merrick—once the terror of Leicester’s streets—was embraced by London society.

The Final Sleep

By 1889, Joseph’s health was failing. His head had grown heavier; his heart was weak. He moved with difficulty, needing help to dress and eat.

On April 11, 1890, nurses found him dead in bed. He had finally lain flat, his head resting on the pillow like a normal man. Treves’s autopsy concluded that the weight of his skull had dislocated his neck, killing him instantly.

“He died,” Treves wrote, “because he wished to sleep like other people—the pathetic but profound desire of his life.”

The Afterlife of a Legend

Treves had Merrick’s skeleton preserved for medical study and his soft tissue buried at the City of London Cemetery. During World War II, most of his preserved remains were destroyed by bombing. Only the skeleton survived, housed today at Barts and The London School of Medicine—not on public display, but still studied by scientists seeking the cause of his deformities.

For decades, doctors debated his condition: Proteus syndrome, neurofibromatosis, or a combination of both. DNA testing has never given a conclusive answer.

Even Merrick’s name remains part of the mystery. Treves inexplicably referred to him as “John Merrick” in his memoirs—a mistake that persists in popular culture to this day.

The Man Beneath the Mask

Victorian society condemned the freak shows that once displayed Merrick, yet continued to treat him as a living exhibit—only now within the refined walls of a hospital. The hypocrisy was glaring. As one critic noted, “The difference was only the audience.”

Yet through it all, Joseph maintained dignity, faith, and gentleness. He created art, cherished friendship, and never ceased to hope for normalcy.

His tragedy was not his deformity, but the world’s inability to see beyond it.

A Human, Not a Monster

More than 130 years after his death, Joseph Merrick still challenges our ideas of beauty, humanity, and compassion. His story endures not because of his abnormalities, but because of his grace in the face of unimaginable cruelty.

He was not the Elephant Man. He was simply a man—intelligent, kind, and yearning to belong.

And in the end, the thing that killed him was not disease or deformity, but the most human desire of all: the wish to be normal, if only for one night.