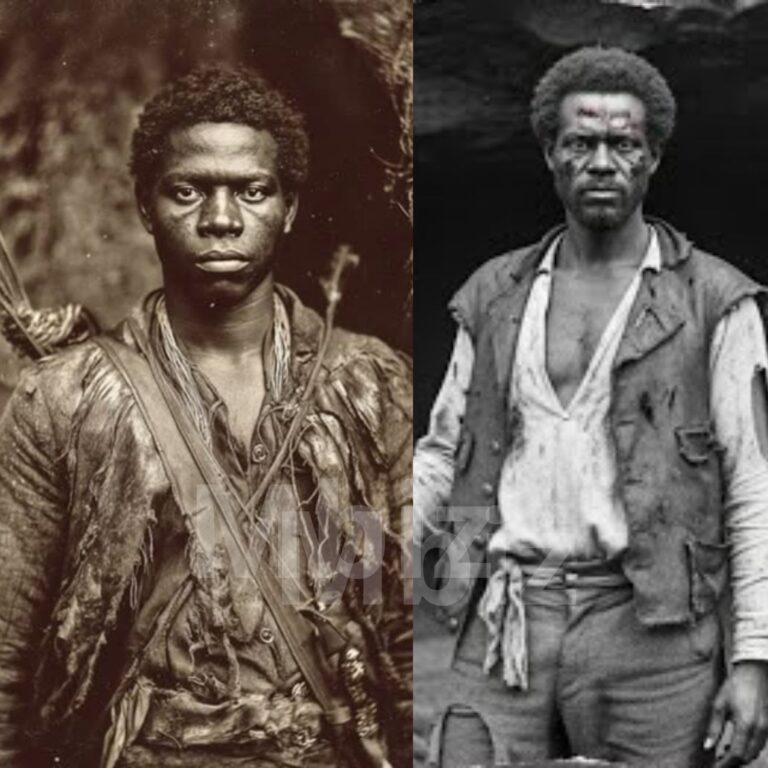

The Slave Who Vanished Into the Mountains — Until His Enemies Began to Disappear (1842)

The year was 1842 when a man named Elias Turner vanished into the Blue Ridge Mountains. At first, there was nothing unusual about it—enslaved people fleeing bondage was a grimly common occurrence across the antebellum South. But what followed in the months after Turner’s disappearance would haunt Wilkes County for generations.

The pursuit of one fugitive turned into something far darker. For as the search parties went into the mountains after Turner, they began to vanish—one by one—until the line between history and haunting blurred forever.

A Routine Escape That Wasn’t

The first record of Turner’s disappearance is a simple entry in plantation owner Jeremiah Caldwell’s ledger, dated March 2, 1842:

“Negro man Elias absconded this day.”

A routine notation—until the handwriting stopped abruptly halfway through the page, as though something had interrupted the man mid-sentence.

The Caldwell Plantation, located about twenty miles west of Wilkesboro, sprawled across eight hundred acres of tobacco fields and dense northern woodlands. It was here that Turner had worked for nearly a decade. Official records described him clinically—male, 30 years of age, sound of mind and body, valued at $800.

But accounts collected decades later told a different story. Turner, witnesses said, was unlike the others. He spoke little, but his silence carried weight. His eyes, one former house slave remembered, “looked through you like he was seeing something you didn’t want seen.”

By early 1842, after years of cruelty, starvation, and overwork, Turner’s quiet watchfulness began to disturb the Caldwell family. In February, he was caught stealing extra rations from the storehouse—a desperate act in a year when frost had destroyed crops and hunger gnawed at slave and master alike. His punishment was severe: seven days locked in the plantation’s root cellar, a dark, narrow chamber half-flooded with groundwater.

When Turner emerged, something in him had changed. He no longer spoke. He no longer bowed. He only smiled—softly, strangely—whenever his master’s family passed by.

The Night of the Storm

On the night of March 1, 1842, a violent storm swept the foothills. Lightning struck a storage shed, setting fire to the slave quarters. Amid the confusion and rain, Elias Turner vanished.

By dawn, Jeremiah Caldwell had assembled a posse—Overseer Thomas Whitaker and five men, aided by bloodhounds—to hunt the fugitive. They expected to bring him back in chains within a day.

They never returned.

The First Vanishing

Caldwell’s letters to his brother in Richmond reveal growing unease:

“The men have gone into the high country. A messenger reported they found tracks, but that was a week ago. No word since.”

After two weeks, Caldwell sent a second, larger search party—ten men led by his son James Caldwell. James’s diary, later recovered from the ruins of the plantation, recorded their final days.

March 20. Found remnants of the first camp. No bodies. The dogs refuse to track further. One howls at night toward the mountains as though answering a call.

March 25. Found a cave entrance. Inside: scraps of cloth, markings carved into the rock—circles, lines like roots. Frederick says we’ll go inside tomorrow. I wish he would change his mind.

That was the last entry. None of the men were ever seen again.

The Sheriff’s Report

By April, panic spread through Wilkes County. Fifteen men—including landowners and overseers—had disappeared. Sheriff William Donnelly requested state militia aid, writing, “Local superstition now reigns. There is talk of vengeance from beyond the grave.”

The militia arrived, scouring the mountains for weeks. They found abandoned camps, burned torches, and an eerie clearing where the ground looked freshly disturbed—“as if for shallow graves,” one scout wrote. In a crude shelter nearby lay a collection of belongings: buttons, watches, and tobacco pouches, all belonging to the missing men.

Nothing else.

Madness at Caldwell Plantation

With his overseer and son gone, Jeremiah Caldwell began to unravel. Neighbors reported hearing him shouting at unseen figures near the woods at night. His wife, Martha, grew hysterical, claiming to hear footsteps above her bed when no one was there.

On September 3, 1842, she was found dead at the foot of the staircase. The coroner called it an accident. But servants whispered that hours before her death, she’d been heard arguing with a man’s voice—though Jeremiah was away in town.

The next morning, Caldwell sold the plantation for half its worth and fled to Richmond, Virginia. Six months later, he was found dead in his rented room, face contorted in terror, fingernails torn as if he’d tried to claw through the wall. The coroner noted mountain clay beneath his nails—though there was none for miles around.

What Happened in the Cellar

For a century, the Turner case remained folklore—until a 1965 archaeological team unearthed the Caldwell root cellar. Beneath its stone floor, they discovered an ancient fissure leading into a network of caves.

Inside the nearby mountain, they found human remains—eight adult males, their bones deliberately arranged in circular patterns. The skulls had been positioned around a ninth, distinct skull of African descent.

The report concluded only: “Evidence suggests ritual significance.”

The cave was resealed. The investigation quietly shut down.

The Forgotten Letter

One year later, a researcher uncovered an 1878 deposition by an elderly woman named Rebecca Harris, who had lived on a neighboring plantation. Her words offered the most chilling explanation of all:

“People think Elias found something evil in that cellar. But he didn’t. He already knew. What he learned down there was patience. He told me once the mountains got long memories—longer than any man’s. When he ran, he didn’t just go into them hills. He became them.”

The Physician’s Journal

In 1964, another document surfaced: the medical journal of Dr. Lawrence Pearson, who treated the Caldwells before Turner’s escape.

His entries painted a house unraveling from within:

January 1842: “The son, James, claims to see Elias standing by his bed each night. He wakes screaming.”

February 10: “Martha confided that Jeremiah’s punishment went beyond whipping. She trembled as she spoke. Something unspeakable occurred in that cellar.”

February 28: “Overseer Whitaker collapsed at supper, raving that they’d ‘let something out’ of the dark. Mr. Caldwell silenced him. I left that place with dread in my heart.”

Whatever happened in that cellar, even before Turner escaped, had already begun to unmake the Caldwells.

The Mountain’s Language

Later investigations revealed that the root cellar stood directly above an uncharted cave system stretching for miles beneath the Blue Ridge foothills. The limestone tunnels connected the Caldwell property to distant ravines and hidden valleys—providing Turner, if he survived, a secret highway through the mountains.

Archaeological findings also uncovered signs of African and Cherokee artifacts coexisting in an isolated valley nearby. Historians now believe Turner may have found refuge among the “hidden people”—Cherokee who refused removal during the Trail of Tears—and that together they used these passages to strike back at their oppressors.

The Fire and the Note

In 1843, a cabin belonging to Caldwell’s cousin, Daniel Roberts, burned to the ground. Roberts was found dead inside—trapped, unable to escape. Carved into the cabin door was a strange symbol, identical to those later found in the mountain cave.

Clutched in the dead man’s hand was a charred scrap of paper:

“The mountain remembers what you did in the cellar.”

The Reverend’s Warning

That same year, Reverend Silas Montgomery, who had often preached at Caldwell’s plantation, vanished on his route between parishes. His horse returned without him. In his abandoned Bible, one verse had been circled in soil mixed with blood:

“And there was a great cry in Egypt; for there was not a house where there was not one dead.”

Montgomery’s final journal entry read:

“I dreamed of Elias standing at my bedside, silent, watching. When I woke, there was mud on my floor. It has not rained in weeks.”

The Mountain That Remembers

In the decades that followed, the story of Elias Turner became a local legend—a cautionary tale whispered around fires and over fences.

Folklorists recorded elders saying he had “made a bargain with the mountain itself,” trading his suffering for the power to move through shadow and stone.

Archaeologist Dr. Howard Mitchell, who investigated the caves in 1965, ended his field notes with one haunting line:

“The pattern repeats. The mountain remembers.”

Echoes in the Modern Age

In 1967, three college students disappeared while hiking near the old Caldwell site. Their camera, recovered from their abandoned camp, showed a final image: a tall, motionless figure watching from a distant ridge.

The site of their camp lay directly above an unmapped cave—the same system that had swallowed the Caldwells more than a century before.

In 1969, historian Dr. Edward Coleman vanished while researching a book on the Turner case. His last journal entry read:

“Breakthrough imminent regarding cellar excavation. He’s watching me write this.”

The Darkness Beneath

Today, the Caldwell land lies within protected forest. The ruins are overgrown, the cellar sealed, the trails unmarked. But hikers still report strange whispers near dusk—soft voices calling their names, promising rest after a long journey.

Those who follow them deeper into the woods sometimes find a narrow path that wasn’t there before… and, at the end, a cave mouth marked with curious symbols.

They say if you listen closely, you can hear breathing inside. And if you linger too long, you may glimpse a face in the dark—hollow-eyed, smiling faintly.

A man who vanished into the mountains in 1842… and never truly left.

Because perhaps the most terrifying possibility is not that Elias Turner died, but that he became something else—something that watches, waits, and remembers every cruelty ever buried in those mountains.