The Fire That Ended an Empire

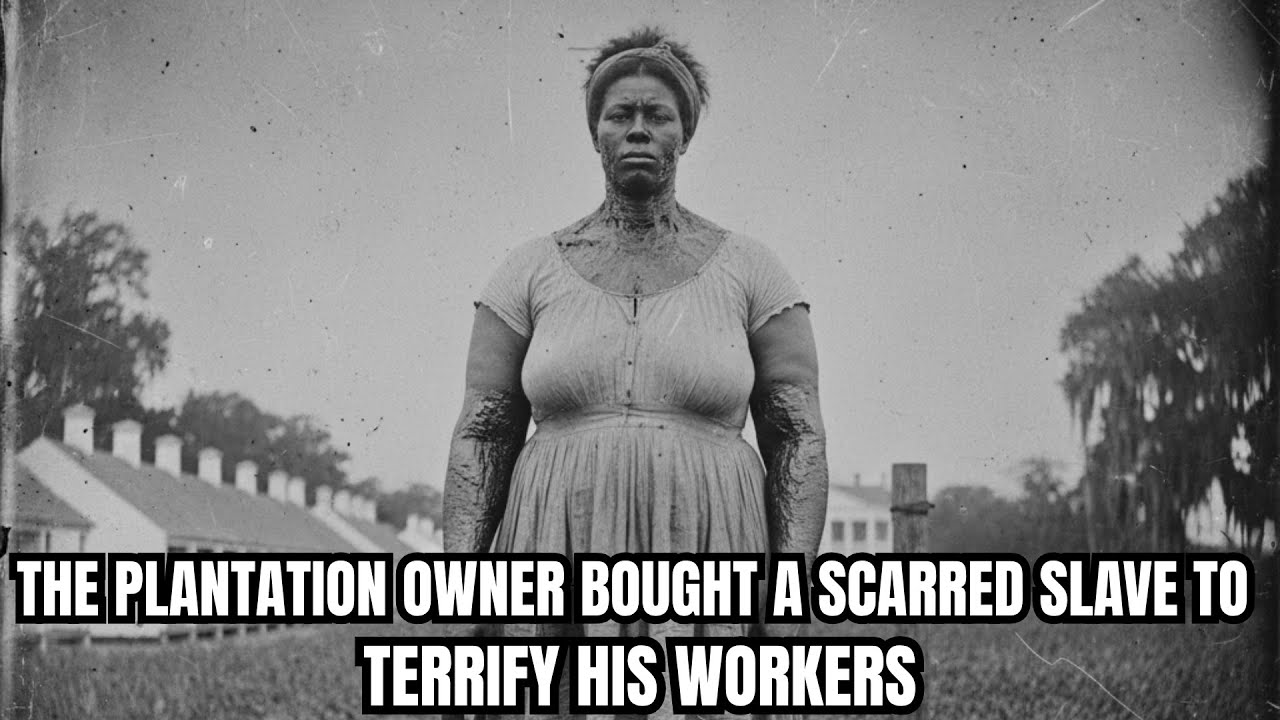

On the morning of August 3, 1847, the enslaved workers of Blackwood Estate in rural Georgia gathered in stunned silence before a sight they would never forget.

The mansion—the grand three-story Georgian home that had dominated the Oconee River valley for nearly forty years—was gone. Nothing remained but a smoking skeleton of brick and char. Inside those ruins, seven bodies were found: Harrison Blackwood, his wife, their children, and several relatives.

All were discovered near sealed doors and windows. They had tried to escape. Someone had locked them inside.

For weeks, the region buzzed with rumors. Some said it was an accident. Others whispered it was rebellion. But the truth was far stranger—and far more disturbing.

Because the prime suspect was not a man.

It was a woman—an enslaved woman—burned, scarred, and feared by all.

Her name was Dina. And the deeper investigators dug into her story, the more they realized that behind her monstrous appearance hid one of the most brilliant and ruthless resistance operations in Georgia’s history.

The Monster of Blackwood Estate

To outsiders, Harrison Blackwood’s plantation represented Southern order and prosperity: 2,400 acres of cotton, over 180 enslaved people, and profits that made Blackwood one of the wealthiest men in the county.

He called his methods “scientific management.” But what that meant, in practice, was control through fear.

In 1843, after two of his enforcers were mysteriously killed, Blackwood sought someone who could terrify without question—a being whose very presence would crush the spirit of rebellion.

He found her in Savannah, at a slave auction for “special cases.”

When Dina stepped onto the platform, people screamed.

She was six foot one, her body a map of old fire scars, her face frozen in a mask of melted flesh and resilience. She had been burned alive as a child in a tobacco barn fire and survived—if survival was the right word for someone who had been made an object of horror.

Blackwood saw not a person, but a tool. He bought her for half the price of a field worker and brought her home to be his executioner.

The Woman They Called Death

Blackwood gave Dina a simple order:

“You will punish the disobedient. You will make them fear me more than they fear God.”

And she did.

Her first public whipping silenced the plantation. Her height, her scars, her expressionless precision—she became a living symbol of pain. Mothers shielded their children’s eyes when she passed. Men crossed themselves.

Within a month, discipline improved by 60%.

To the white overseers, she was perfection.

To the enslaved, she was terror.

And to Harrison Blackwood, she was proof that fear worked.

But no one—not even Blackwood—understood that Dina’s silence was not submission. It was strategy.

The Secret Beneath the Scars

Every night after the beatings, Dina requested permission to “monitor recovery.” Blackwood agreed. After all, he didn’t want to lose valuable labor to infection.

But behind the closed door of her cabin, Dina was not punishing anymore.

She was healing.

She cleaned wounds, applied herbs, and whispered secrets. She taught the wounded how to read the land, where the rivers met, what stars to follow, and—most dangerously—how to disappear.

Because Dina’s cabin, the place everyone feared, was not a torture chamber.

It was an underground classroom.

And over four years, from 1843 to 1847, she used her position as executioner to orchestrate the escape of forty-seven enslaved people—more than a quarter of the plantation’s workforce.

Her victims were her recruits. Her brutality was her disguise.

Her scars were her camouflage.

A Conspiracy Hidden in Plain Sight

Investigators would later find that Dina’s system was meticulous.

Those who vanished were listed as dead, their clothes left near rivers, their names crossed off ledgers.

Those who were “buried” were buried in empty graves.

Dina’s knowledge came from everywhere—a white girl who had once taught her to read, books stolen from the Blackwoods’ library, and whispered rumors about abolitionist networks in the North.

She memorized maps.

She forged travel passes.

She learned how slave catchers thought—and how to fool them.

And when her “students” left, she ensured the plantation would never suspect a thing. The perfect alibi: fear.

The Night of Fire

By 1847, Dina knew her time was running out. Harrison Blackwood was planning to expand the plantation—more land, more overseers, more eyes watching everything.

Her secret network couldn’t survive that. So Dina made a choice.

If she couldn’t keep saving lives in secret, she would end the system in one final act.

What happened that August night is known only through the surviving evidence: barricaded doors, spilled lamp oil, drugged overseers, and one buried metal strongbox that investigators later found containing lists of names, coded maps, and a letter.

When the fire started, the Blackwood family was locked inside.

When it ended, the plantation’s enslaved population was free—or gone.

Witnesses later claimed Dina appeared before the remaining workers as the mansion burned behind her, her face lit orange by the flames.

“The Blackwoods are dead,” she said.

“Those who want freedom—follow me now.”

Forty-three people left with her.

They reached Savannah by dawn and boarded a ship bound for Philadelphia.

Dina went with them—and vanished.

The Strongbox and the Letter

Weeks later, federal investigators unearthed a metal box buried near Dina’s cabin. Inside were the names of every person she had saved, the routes they took, and one final message written in a careful, scarred hand:

“I was purchased to be a monster. Instead, I became something far more dangerous.

The tools you create can turn in your hands.

The monsters you make can learn to think.

I was your executioner.

I became your judge.”

The Blackwood Fire became one of the most infamous unsolved cases of the antebellum South. Officials labeled it “The Blackwood Conspiracy.” Slaveholders across Georgia panicked. Some plantations disbanded their internal “enforcer” systems entirely, terrified that their own instruments of terror might rise against them.

The Woman Who Became a Legend

Dina was never found. But abolitionist archives in Philadelphia later recorded the arrival of a tall, heavily scarred woman in late 1847 who helped dozens of newly freed people start new lives.

She lived quietly under another name, working in textile mills, then as a midwife. She died in 1872—free, surrounded by hundreds who owed their freedom to her.

At her funeral, a minister who had known her said:

“They made her into a monster to maintain bondage.

She became the monster who destroyed it.”

The Ghosts of Blackwood

The Blackwood estate was never rebuilt. Locals say that every August, when the night air is heavy and the river runs slow, you can still smell smoke drifting through the fields—and hear faint voices crying for mercy.

But perhaps those aren’t ghosts of the dead.

Perhaps they’re echoes of the living—the ninety souls who walked into freedom because one woman refused to be what her masters made her.

She was feared.

She was scarred.

She was the monster they created.

And the savior they never saw coming.