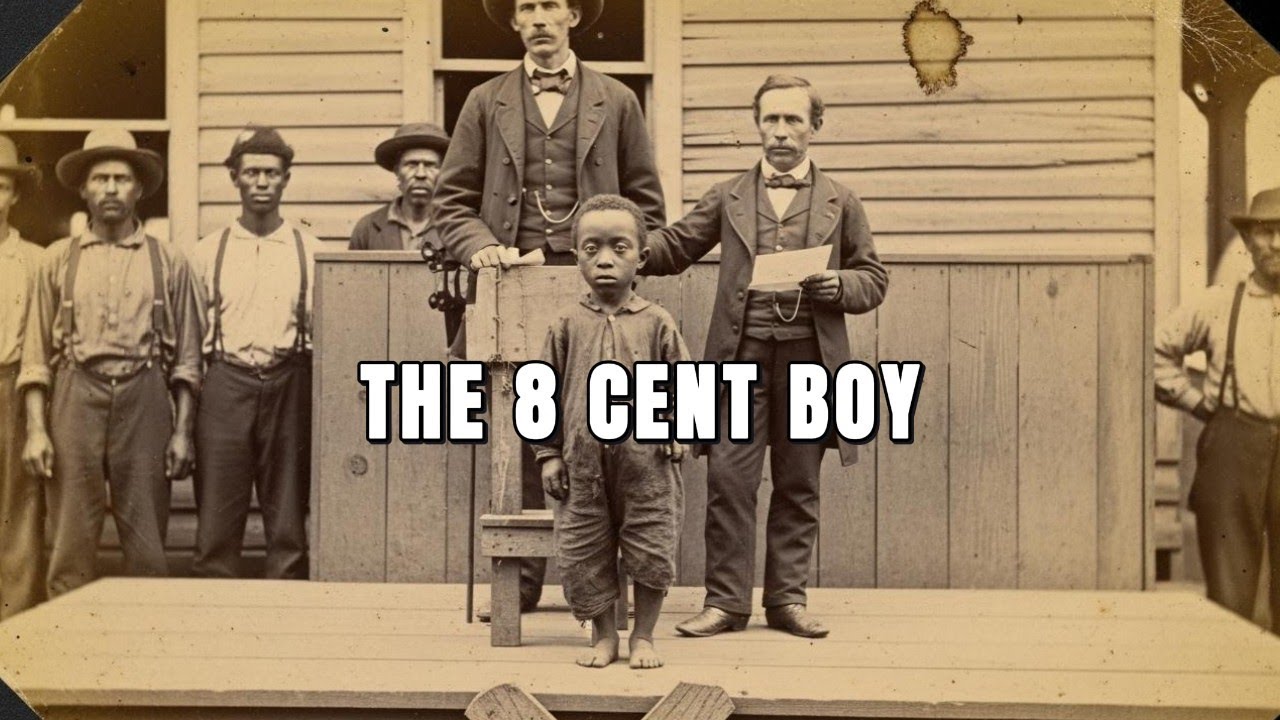

(Georgia, 1851) Dwarf Slave Boy Bought for 8 Cents Crushed His Master’s sᴋᴜʟʟ with a Cotton Press

On the morning of September 14, 1851, workers arriving at the Hateville Cotton Processing Facility in southern Georgia made a discovery so horrifying that even seasoned men of the trade refused to speak of it for decades. Beneath the massive iron press that transformed raw cotton into compact bales lay the overseer, Tobias Straud, his skull crushed beyond recognition.

The machine’s wheel had been turned exactly seventeen times—enough pressure to compress two hundred pounds of cotton into a single bale, or to reduce a human head to something less than three inches thick.

But it was what the sheriff found three days later that turned this killing into one of the most disturbing unsolved cases in antebellum history: a small wooden step stool, built for someone no taller than four feet. The murder weapon had been operated by a child.

And according to plantation records later uncovered and sealed by the Georgia Historical Society, that child had been purchased eight months earlier for eight cents—the price of a damaged tool.

The Overseer and the “8-Cent Boy”

In 1851, Hateville existed as a crossroads town serving Georgia’s booming cotton empire. The processing facility at its center belonged to Cyrus Gantry, a businessman who made his fortune not from growing cotton, but from compressing and shipping it to the textile mills of New England. His overseer, Tobias Straud, was a man known for two things: efficiency and cruelty.

Straud’s workers feared him more than Gantry himself. He lived in a small house beside the facility, close enough to hear the machines groan through the night and to ensure no one dared rest. He kept meticulous ledgers on every enslaved laborer — recording hours, productivity, and “corrections” administered with his leather strap.

But Straud had another obsession: he collected broken things. His house was filled with cracked pottery, broken clocks, warped furniture. He once said he found “value in what others discard.” That philosophy extended to people.

At a small estate auction in February 1851, Straud purchased a child for eight copper pennies. The boy, recorded only as “Small Thomas,” was roughly eleven years old, no taller than four feet, his spine and limbs deformed by a congenital condition. The auctioneer tried to sell him as “a household helper,” but no one bid until Straud spoke: “Eight cents,” he said flatly.

Laughter followed. Then silence. The sale was recorded — a human life exchanged for less than the price of a pound of nails.

“You’ll work at the cotton facility,” Straud told the boy. “And you’ll earn your worth.”

The Sign Around His Neck

At the facility, Straud’s fascination with his new purchase became a spectacle. He forced the boy to wear a wooden sign that read “8-Cent Boy.”

“He needs to know his value,” Straud told anyone who objected. “When he earns it back, I’ll take it off.”

By his own calculations, that would take seven years—if the boy survived that long.

Thomas’s tasks were brutal: crawling beneath the presses to clear jammed gears, fetching tools from impossible crevices, cleaning the machinery with rags soaked in lye. He slept in the barn on a thin blanket and ate what the others spared him.

Yet against all odds, he adapted. The boy moved through the machinery like a ghost, memorizing its rhythms and sounds. Under the quiet tutelage of an older worker known as Prophet, he learned which gears to oil, which bolts to tighten, which levers to avoid.

Over months, his blank stare hardened into something else — calculation.

The Press and the Plan

By midsummer 1851, Thomas understood the machines better than Straud himself. He could fix jams that halted production, sense imbalance by sound, and tell precisely how many rotations of the great wheel produced the perfect cotton bale.

In July, a drive chain snapped inside the main press. The cavity was too narrow for an adult to reach. Straud ordered Thomas to crawl in. Prophet protested: “Sir, it’s too dangerous.”

Straud waved him off. “Boy goes in. I’ll watch him.”

For nearly an hour, Thomas lay inside that iron coffin, inches from the gears that could crush him instantly. When he emerged, grease-blackened and trembling, he dragged the heavy chain behind him like a shackle.

“See?” Straud said, smirking. “Even things bought cheap can prove their worth.”

From that day forward, Thomas’s gaze lingered on the press longer than anyone thought natural. He watched it the way others watched the stars—studying, measuring, waiting.

Murder in the Cotton House

In the early hours of September 14, Straud made his final rounds of the night shift. The press was still, the air thick with heat and oil. Sometime between 3 a.m. and dawn, the machine came alive.

When morning workers arrived, they found the press frozen midcycle. Oil lamps still burned. On the bed of the machine lay Tobias Straud — his body untouched below the neck, his head obliterated into pulp. The wheel had been turned seventeen times.

Beside the press stood the step stool — a handmade structure of scrap lumber, just high enough for a child.

Sheriff Edmund Howell arrived within the hour. “Circumstances most disturbing to contemplate,” he wrote in his report. The child was missing. His corner of the barn lay neatly arranged: blanket folded, a riverstone trinket, and the wooden sign—the “8-Cent Boy” placard—left carefully atop his crate.

The Vanishing

The search was immediate and relentless. Rewards were posted. Slave catchers scoured the countryside. Within a week, tracks matching Thomas’s twisted gait were found near Redemption Creek, leading into shallow water and vanishing.

A copper penny was found pressed into the earth beneath a tree root — one of eight.

“Maybe he left it to show what he was worth,” Cyrus Gantry muttered when Sheriff Howell showed him the coin.

Whether Thomas drowned or escaped, no one could say. Howell’s private notes, unearthed decades later, tell a different story: “The boy did not drown. Someone helped him. Someone wanted him free.”

The Silence of Hateville

In the weeks that followed, Hateville changed its story. The newspapers, once lurid with headlines about “a savage murder,” suddenly fell silent. Gantry paid the editor to bury the coverage. The processing facility reopened within two weeks.

But something about the murder gnawed at him. Among Straud’s belongings, Gantry found the overseer’s private notebook — filled with obsessive entries about the boy:

“August 29. The 8-cent boy shows remarkable understanding of the press mechanism.”

“September 8. He asks how much force is required to crush 500 lbs of cotton.”

“September 13. Tomorrow I will remove the sign. Perhaps even teach him to read.”

Gantry read those lines, then burned the journal. “Some debts can’t be repaid,” he told his wife. “Only balanced.”

What Really Happened That Night

Among the enslaved community, another version of events circulated — one that could never be spoken aloud.

According to whispers passed down for generations, Thomas had not acted alone. The other workers had not turned the wheel — but they had turned away. They had loosened a bolt here, distracted Straud there, created silence where there should have been witness.

The plan had been simple. Straud found a mechanical fault — one Thomas had deliberately engineered. When the overseer bent over the press to inspect it, the boy pulled the safety lever. The plate dropped just enough to trap him.

After that, Thomas worked patiently, methodically, for over an hour — one quarter turn at a time, seventeen rotations in total. The sound of the press masked everything.

The others kept their eyes fixed on their own stations, mastering the most vital survival skill of all: not seeing.

The Cabin in the Woods

Thirty-eight years later, in 1889, railroad workers clearing land twelve miles from Hateville found a decaying cabin. Inside lay the skeletal remains of a child with severe spinal deformities. Next to the bones: a tin cup, fragments of clothing, and eight copper pennies arranged in a perfect circle.

An elderly freedwoman named Patience Freeman came forward after reading the story in the Atlanta Constitution. She told reporters she had known the boy.

On the morning after Straud’s death, she said, she saw Thomas emerge from Redemption Creek—wet, limping, alive. She hid him in an old fugitive’s cabin and brought him food for weeks until he died, “peaceful, like he’d finally rested.”

Before she buried him, she said, he had arranged the pennies himself. “He wanted to leave the world on his own terms,” she told the paper. “He wanted to show them what eight cents could do.”

Legacy of the 8-Cent Boy

No official records ever acknowledged Thomas’s existence beyond the auction bill. The Hateville facility burned down in 1923, leaving no trace of the iron press. Today, the site is a parking lot with no marker.

But among descendants of Georgia’s enslaved communities, his story endures — retold as both warning and legend. In 1937, a former slave interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project recalled it this way:

“We told that story to our children to teach them two things. First, that the system would break you if it could. Second, that even when you small, even when they say you worth eight cents, you still got power if you know how to use it.”

Thomas’s revenge did not end slavery, but it cracked the illusion of invulnerability that sustained it. His life — and his death — became an emblem of the impossible choices faced by those denied their humanity.

The Final Question

In the end, the story of the 8-Cent Boy leaves only questions:

Was it murder, or justice? Did he die fleeing, or free?

What is the value of a life priced at eight copper pennies?

History, like that iron press, compresses the truth under its weight — until only what we choose to remember remains.